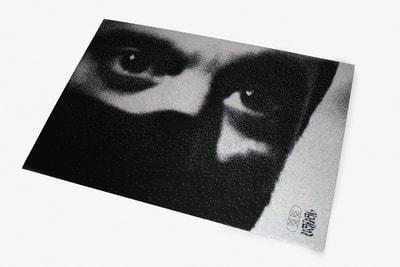

LABYRINTH - LES LARMES DE MINOSLightbox photography, 120 x 80cm

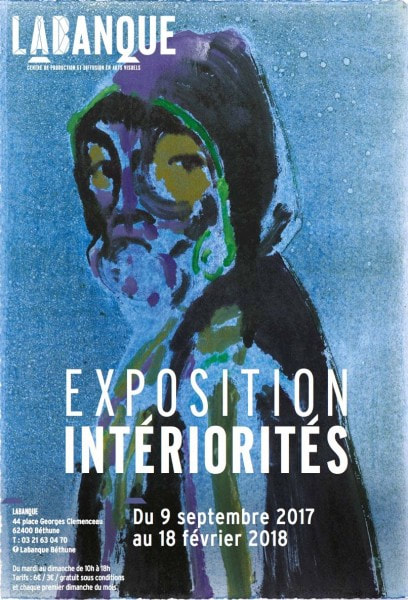

Stroboscopic lights, seats Sound installation & composition for 8 speakers, 90' (in collaboration with Jules Wysocki) Produced by Labanque / ADAGP For the exhibition Intériorités, Frédéric D. Oberland surrounds the basement of Labanque art center in Béthune with a large sound installation accompanied by one of his photographs, 'Les Larmes de Minos' / 'The Tears of Minos', which refers to the myth of the Minotaur. 90 minutes of musical strolling divided into eight tableaux and spatialized on a set of eight speakers are building, according to a certain psychogeography, a labyrinthine course. We meet the ghosts of Dante Aliegheri and the Minotaur, stroboscopes and reflections on the river that leads from the known to the unknown. Immersed as if he were in the bowels of the earth, the spectator is invited to experience the murmurings of duration. 2017: Exhibition Intériorités' - 'La Traversée des Inquiétudes' at Labanque art center, Bethune, France 2017: Artist talk with Mathilde Girard at Galerie Escougnou-Cetraro, Paris, France La Traversée des Inquiétudes is a trilogy of exhibitions freely inspired by Georges Bataille and curated by Léa Bismuth. With Bas Jan Ader, Chantal Akerman, Hans Bellmer, Jacques-André Boiffard, Eugène Von Bruenchenhein, Charlotte Charbonnel, Clément Cogitore, Marguerite Duras, Marco Godinho, Oda Jaune, Atsunobu Kohira, Pierre Molinier, Romina De Novellis, Frédéric D. Oberland, Florencia Rodriguez Giles, Anne Laure Sacriste, Markus Schinwald, Pia Rondé, Fabien Saleil, Gilles Stassart, Claire Tabouret, Sabrina Vitali, Daisuke Yokota, Jerome Zonder, Zorro. |

'LABYRINTH' soundtrack out now via NAHAL RECORDINGS imprint -> ORDER VINYL (+exclusive silkscreen print by Atelier Huit Mains) / DIGITAL